Knowledge Breadth versus Depth

Mark Richards, my co-presenter in the Software Architecture Fundamentals video series, is a a deeply knowledgable architect who doesn’t blog much, so I’m presenting this idea on his behalf. He first exposed me to the Knowledge Pyramid while we were preparing Software Architecture Fundamentals Part 1 and it resonated with me immediately.

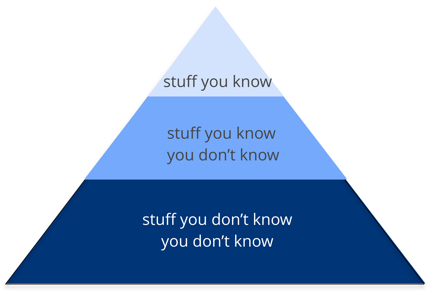

With Mark’s Pyramid, he makes a keen observation about career-long knowledge acquisition, particularly the transition from developer to architect. First, consider this knowledge pyramid, encapsulating all the knowledge on earth:

Figure 1: All Knowledge

Any individual can partition that knowledge into three sections: Things You Know, Things You Know You Don’t Know, and Things You Don’t Know You Don’t Know. A deveoper’s early career focuses on expanding the top of the pyramid, to build experience and expertise. This is the ideal focus early because you need more perspective, working knowledge, and hands-on experience. Expanding the top incidentally expands the middle section; as you encounter more technologies and related artifacts, it adds to your stock of Things You Know You Don’t Know.

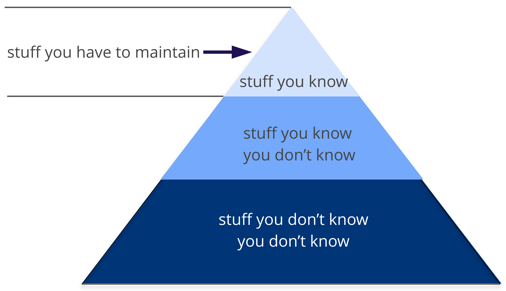

Figure 2: Expertise must be maintained

Expanding the top of the pyramid is beneficial because expertise is valued. However, the Things You Know are also the Things You Must Maintain–nothing is static in the software world. If you become an expert in Ruby on Rails, that expertise won’t last if you ignore it for a year. The things at the top of the pyramid require time investment to maintain expertise. Ultimately, the size of the top of your pyramid is your technical depth.

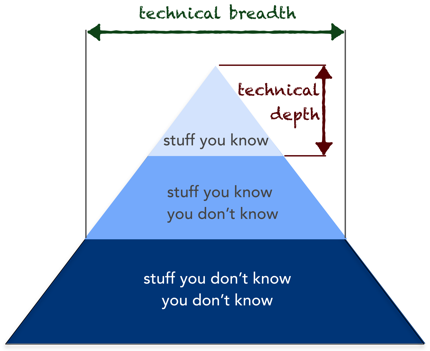

However, the nature of knowledge changes as you start in the architect role. A large part of the value of an architect is a broad understanding of technology and how it can be used to solve particular problems. For example, as an architect, it is more beneficial for me to know that five solutions exist for a particular problem than to be a singular expert in only one. The most important parts of the pyramid for architects are the top and middle sections; how far your middle section penetrates into the bottom section represents your technical breadth.

Figure 3: What You Know is your technical depth, How Much You Know is your technical breadth

As an architect, breadth is more important than depth. Because architects must make decisions that match capabilities to technical constraints, a broad understanding of a wide variety of solutions is valuable. Thus, for architects, the wise course of action is to sacrifice some of your hard won expertise and use that time to broaden your portfolio.

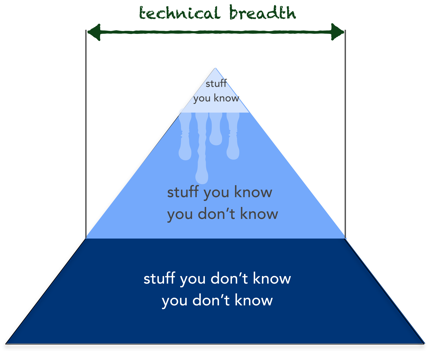

Figure 4: Enhanced breadth and shrinking depth for the architect role.

Some areas of expertise will remain, probably around particularly enjoyable technology areas (mine is programming languages), while others usefully atrophy.

Mark’s pyramid illustrates how fundamentally different the role of architect compares to developer. Developers spend their whole career honing expertise, and transitioning to the architect role means a shift in that perspective, which many architects find difficult. This in turn leads to two common dysfunctions: first, an architect tries to maintain expertise in a wide variety of areas, succeeding in none of them and working themselves ragged in the process. Second, it manifests as stale expertise–the mistaken sensation that your outdated information is still cutting edge. I see this often in large companies where the developers who founded the company have moved into leadership roles yet still make technology decisions using ancient criteria (I refer to this as the Frozen Caveman Antipattern).

As an architect, focus on technical breadth so that you have a larger quiver from which to draw arrows. If you are transitioning roles from developer to architect, realize that you may have to change the way you view knowledge acquisition. Balancing your portfolio of knowledge regarding depth versus breadth is something every developer should consider throughout their career.

Thanks to Martin Fowler, Jeff Norris, Kief Morris, Rouan Wilsenach, and Stuart Rolland for useful feedback on early drafts.